I really like ancient traditions. I’d say I seek them out. I remember when I was a kid, my mom used to make a lot of things out of blueprints. Back then it was just COOL! You may know it from costumes or maybe you have a tablecloth made from it at home like I do. I think blueprint has a lot of potential and is timeless! I’m glad there are still workshops like the one in Strážnice where you can learn about our traditions. I have been to Strážnice several times, but I have only just visited the workshop.

WHERE DID THE BLUEPRINT COME FROM ANYWAY

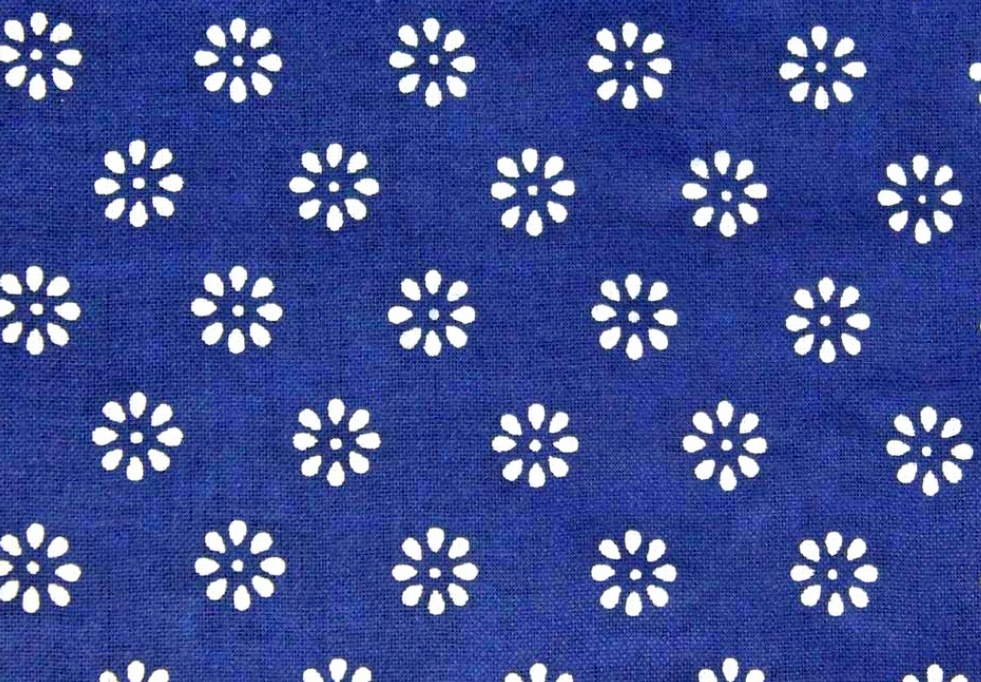

The blueprint is characterized by a white pattern on a dark blue background. It is a technologically preserved rarity and it is no wonder that its handmade production was inscribed on the UNESCO heritage list in 2018.

Do you think that the blueprint originated here in Moravia? Oh, no. It’s a 3,000-year-old technology originally from China. From there, indigo dyeing spread throughout Asia. It came to Europe in the 18th century thanks to seafarers. Of course, blueprinting was first available to the nobility and wealthy bourgeoisie. They used it for wallpapering and upholstery. Originally, indigo was imported, but because it was expensive, synthetic indigo was used. It has the same properties. But for example, when I visited Japan , I came across the natural one.

BLUEPRINT WORKSHOP

There used to be blueprint workshops in almost every village. But what about now? Now you won’t find many blueprint workshops in the Czech Republic. The one in Strážnice is basically one of the two (the other is still in Olešnice) last establishments of its kind in the Czech Republic.

I was really looking forward to coming here. The visit is connected with a demonstration of traditional production, which has not changed at all since the workshop was founded. We were lucky, because we were accompanied by Gabriela Bartošková, who explained everything very nicely and especially showed us the demonstration. She is able to talk about her work with such enthusiasm that you get the feeling that it is a pity that you do not own such a workshop. 🙂

I like inspiring people and she is one of them. Gábina is the fifth generation of her family business and at 27 years old she became the first trained female printer. She studied fashion design but wasn’t interested in blueprinting at all. She found it uninteresting. Eventually she listened to her mother and tried blueprinting once. And eventually, she became enchanted with blueprinting. I was very interested in her story. She says that printing takes 6 years of learning and dyeing takes 10 years to master. The dyeing is the most challenging part of blueprint making. And she says she’s still on her way to perfection.

A LITTLE BIT OF HISTORY

The Strážnice workshop was founded by Cyril Joch in 1906 with his wife Anna. He then had to enlist and after returning from the war he ran the workshop for another six years. He trained his three sons and taught his nephew Josef Gerstberger in the trade. When he died of tuberculosis of the lungs, his wife took over the workshop. The middle son František Joch and his young wife Milada also started to make blueprints. He eventually inherited the workshop. A fundamental change occurred after the communist takeover, when the workshop’s activities were interrupted for some time. It was only restored thanks to the efforts of the Centre for Folk Art Production. Artists began to cooperate with František Joch, who updated the blueprint patterns and introduced other new modifications of the blueprint. The production increased significantly and, in addition to the couple Milada and František Joch, their son František and Josef Gerstberger also began to participate in the operation of the workshop. Gabriela was trained by her uncle František Joch, a printer and son of the original founder.

HOW IS BLUEPRINTING MADE?

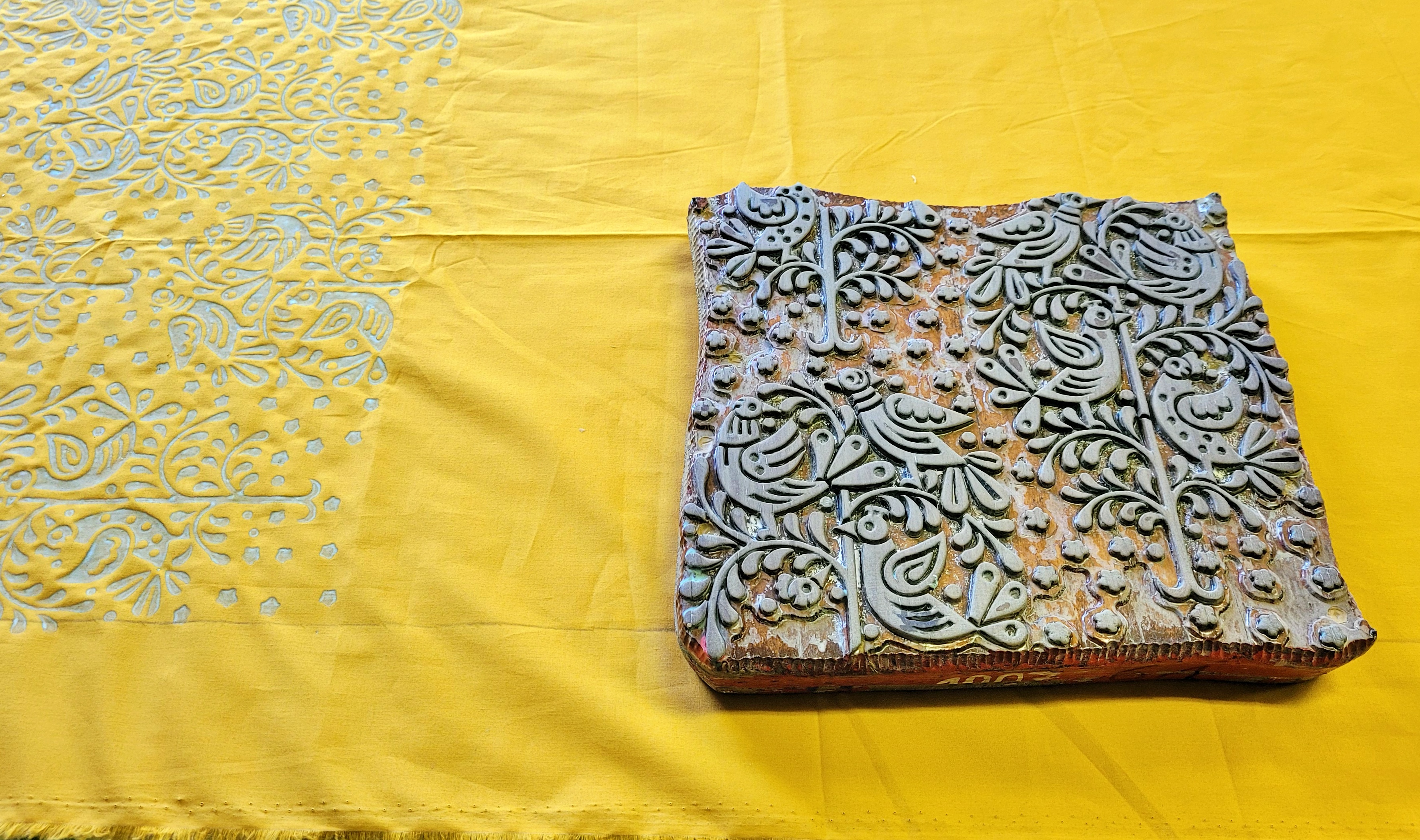

The production of blueprints is time and money consuming. You realise this as soon as you step into the workshop. Few people know that before printing, the fabric is first starched with wheat starch, refined and stretched on tables 5 metres long. Then it’s printed with a special reserve ink, or pop. It’s a kind of mushy light green ink that consists of kaolin, gum Arabic or blue rock. The ratio of these substances is also important, which is the secret that every workshop keeps.

It is cooked in the boiler for 5 to 6 hours. Safety glasses, gloves and a respirator must be worn. It is then left to rest for two months.

The pop is smeared in the crate with a brush called a pincushion. Rubbing is called scratching. Those are the names! They come from the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Each time the moulds are dipped, they are imprinted on the canvas. The sample is tapped on the attached mould to ensure that it is evenly printed. And so it goes on and on.

It reminds me a bit of stamping, but it’s not. You have to keep your attention so you don’t get confused and the pattern follows you. Even though the pattern is dry in about 20 minutes, you need to let the pop harden thoroughly on the fabric, which takes 5 to 10 days.

At the other end of the workshop is a building with a dye house. There is a stone pool which is about 2 metres deep. Inside it has this strange thick blue-violet dye bath. It’s called kypa.

And this is where I find out why it’s so hard to make a blueprint. If the pop or the kypa is done wrong, the colors don’t interact and the printed pattern runs off the fabric. All sorts of beakers are used to measure the bath here. But an experienced dyer can already tell by smell.

Gabriela demonstrated how to dip a strip of cloth into the bath. It has a greenish-yellow colour when pulled out. After a moment, she shows us how the fabric has turned blue. Everything turns blue except the sample. The whole soaking process has to be repeated 5 more times.

The canvas is then washed in an industrial washing machine with a 4% sulphuric acid solution. This dissolves the pop with which the fabric was printed.After weeks, a dark blue base with a white pattern is formed. The acid is not aggressive at all. The textile fibre is not damaged. The canvas is then washed in clean water, dried and passed through an almond. Finally, it’s done! The whole process takes about 3 weeks.

PRINTING MOULDS

Perhaps the most fascinating part of the workshop is the wall with shelves in which wooden printing forms are arranged. They have about 200 moulds in the workshop, but they use about half of them. Some of them are really very old, but ironically they are among the most popular. They are simply timeless.

I learn how to call the different patterns: ‘log, bell, stump or rosemary with a rose’. All the patterns are carved from pear wood. The pear is both smooth and hard. It is also chosen because it has no rings. Some of the forms are pure wood, but I adore the ones with a combination of tiny cloves. I’m amazed because it must have been an incredible pip.

Each mould has a handle at the back that can be held with one hand. The moulds are made of two or three layers to prevent them from curling and to keep them straight. Gabriela gave it to us to try and I must admit that the moulds are quite heavy. I still don’t understand how she can hold them with one hand.

Each mould has nails in the corners – the so-called onzece, which the printer uses to follow the pattern. Basically, he prints by attaching the nail on the mould to the printed nail in the pattern of the cloth, which he follows. However, this is not always easy.

Each mould has nails in the corners – the so-called onzece, which the printer uses to follow the pattern. Basically, he prints by attaching the nail on the mould to the printed nail in the pattern of the cloth, which he follows. However, this is not always easy.

MISTAKES IN BLUEPRINTS AND HOW TO RECOGNIZE THE FAKE ONE?

There are many mistakes about blueprinting. For example, that it is printed with white ink on a blue substrate or that it leaks colour when washed. Basically, there are three rules to spot a fake one.

- First, blueprints are expensive and you can buy a fake one cheaper.

- Secondly, you have to look for honest handwork behind it all, in short the human factor. Of course, printers are only human and so you will find some small imperfection in the binding of the pattern on the fabric. So everything is so original.

- And thirdly, you can tell by the reverse side. The pattern has to shine through, and the fake blueprint is all blue on the reverse side. That means it couldn’t have been soaked in a bath.

HOW TO CARE FOR THE BLUEPRINT

There is no need to worry about the white pattern discolouring in the wash. Immediately after washing, the pattern may look light blue on the wet fabric because the blue colour shines through from the reverse side, but this will disappear after drying. Detergent and tumble drying are not recommended. Otherwise, you can take care of it normally and iron it.

We end the whole excursion with a visit to the shop. There is really a lot to choose from. You have to restrain yourself from buying everything here.

If you liked the article, I would be glad if you share it or leave a nice comment below the article.

I would also like to invite you to join me on na Instagramu and Facebooku.